THE OUTSOURCING HOUSE

WE WILL PROVIDE YOU ALL OF YOUR BOOK KEEPING,PREPARATION OF YOUR FINAL ACCOUNTS,TAX REPORT AND FACILITATE IMPORT AND EXPORT OF GOODS FOR CHEAPER PRICES.

Ad valorem

Ad valorem

An ad valorem tax is one where the tax base is the value of a good, service, or property. Sales taxes, tariffs, property taxes, inheritance taxes, and value added taxes are different types of ad valorem tax. An ad valorem tax is typically imposed at the time of a transaction (sales tax or value added tax (VAT)) but it may be imposed on an annual basis (property tax) or in connection with another significant event (inheritance tax or tariffs). An alternative to ad valorem taxation is an excise tax, where the tax base is the quantity of something, regardless of its price. For example, in the United Kingdom, a tax is collected on the sale of alcoholic drinks that is calculated by volume and beverage type, rather than the price of the drink.

Kinds of taxes

Kinds of taxes

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) publishes perhaps the most comprehensive analysis of worldwide tax systems. In order to do this it has created a comprehensive categorisation of all taxes in all regimes which it covers

Costs of compliance

Costs of compliance

Although governments must spend money on tax collection activities, some of the costs, particularly for keeping records and filling out forms, are borne by businesses and by private individuals. These are collectively called costs of compliance. More complex tax systems tend to have higher costs of compliance. This fact can be used as the basis for practical or moral arguments in favor of tax simplification (see, for example, FairTax), or tax elimination (in addition to moral arguments described above).

Tax incidence

Tax incidence

Economic theory suggests that the economic effect of tax does not necessarily fall at the point where it is legally levied. For instance, a tax on employment paid by employers will impact on the employee, at least in the long run. The greatest share of the tax burden tends to fall on the most inelastic factor involved - the part of the transaction which is affected least by a change in price. So, for instance, a tax on wages in a town will (at least in the long run) affect property-owners in that area.

Transparency and simplicity

Double dividend taxes

Double dividend taxes

In some cases where the economy is not perfectly competitive, the existence of a tax can increase economic efficiency. If there is anegative externality associated with a good, meaning that it has negative effects not felt by the consumer, then the free market will trade too much of that good. By putting a tax on the good, the government can increase overall welfare as well as raising revenue in taxation. This is known as a 'double dividend'.

There are a wide range of goods where there is, or is claimed to be, a negative externality. Polluting fuels (like petrol), goods which incur public healthcare costs (such as alcohol or tobacco), and charges for existing 'free' public goods (like congestion charging) all offer the possibility of a double dividend. This type of tax is a Pigovian tax, sometimes colloquially known as a 'sin tax'. It is worthwhile noting that taxation is not necessarily the only, or the best, method of dealing with negative externalities.

Deadweight costs of taxation

Deadweight costs of taxation

For goods supplied in a perfectly competitive market, tax reduces economic efficiency, by introducing a deadweight loss. In a perfect market, the price of a particular economic good adjusts to make sure that all trades which benefit both the buyer and the seller of a good occur. After introducing a tax, the price received by the seller is less than the cost to the buyer. This means that fewer trades occur and that the individuals or businesses involved gain less from participating in the market. This destroys value, and is known as the 'deadweight cost of taxation'.

The deadweight cost is dependent on the elasticity of supply and demand for a good.

Most taxes—including income tax and sales tax—can have significant deadweight costs. The only way to completely avoid deadweight costs in an economy which is generally competitive is to find taxes which do not change economic incentives, such as the land value tax,[17] where the tax is on a good in completely inelastic supply, a lump sum tax such as a poll tax which is paid by all adults regardless of their choices, or a windfall profits tax which is entirely unanticipated and so cannot affect decisions.

The Economics of taxation

Economics of taxation

In economic terms, taxation transfers wealth from households or businesses to the government of a nation. The side-effects of taxation and theories about how best to tax are an important subject in microeconomics. Taxation is almost never a simple transfer of wealth. Economic theories of taxation approach the question of how to minimize the loss of economic welfare through taxation and also discuss how a nation can perform redistribution of wealth in the most efficient manner.

HISTORY OF TAXATION

History

[

Taxation Levels

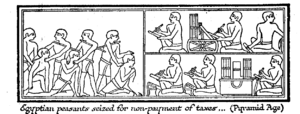

The first known system of taxation was in Ancient Egypt around 3000 BC - 2800 BC in the first dynasty of the Old Kingdom.[11] Records from the time document that the pharaoh would conduct a biennial tour of the kingdom, collecting tax revenues from the people. Other records are granary receipts on limestone flakes and papyrus.[12] Early taxation is also described in the Bible. In Genesis (chapter 47, verse 24 - the New International Version), it states "But when the crop comes in, give a fifth of it toPharaoh. The other four-fifths you may keep as seed for the fields and as food for yourselves and your households and your children." Joseph was telling the people ofEgypt how to divide their crop, providing a portion to the Pharaoh. A share (20%) of the crop was the tax.

In India, Islamic rulers imposed jizya starting in the 11th century. It was abolished by Akbar. Quite a few records of government tax collection in Europe since at least the 17th century are still available today. But taxation levels are hard to compare to the size and flow of the economy since production numbers are not as readily available. Government expenditures and revenue in France during the 17th century went from about 24.30 million livres in 1600-10 to about 126.86 million livres in 1650-59 to about 117.99 million livres in 1700-10 when government debt had reached 1.6 billion livres. In 1780-89 it reached 421.50 million livres.[13] Taxation as a percentage of production of final goods may have reached 15% - 20% during the 17th century in places like France, the Netherlands, and Scandinavia. During the war-filled years of the eighteenth and early nineteenth century, tax rates in Europe increased dramatically as war became more expensive and governments became more centralized and adept at gathering taxes. This increase was greatest in England, Peter Mathias and Patrick O'Brien found that the tax burden increased by 85% over this period. Another study confirmed this number, finding that per capita tax revenues had grown almost sixfold over the eighteenth century, but that steady economic growth had made the real burden on each individual only double over this period before the industrial revolution. Average tax rates were higher in Britain than France the years before the French Revolution, twice in per capita income comparison, but they were mostly placed on international trade. In France, taxes were lower but the burden was mainly on landowners, individuals, and internal trade and thus created far more resentment.[14]

Taxation as a percentage of GDP in 2003 was 56.1% in Denmark, 54.5% in France, 49.0% in the Euro area, 42.6% in the United Kingdom, 35.7% in the United States, 35.2% in The Republic of Ireland, and among all OECD members an average of 40.7%.[15][16]

Tax burden

Direct and indirect Taxes

Direct and indirect

Taxes are sometimes referred to as direct tax or indirect tax. The meaning of these terms can vary in different contexts, which can sometimes lead to confusion. In economics, direct taxes refer to those taxes that are collected from the people or organizations on whom they are ostensibly imposed. For example, income taxes are collected from the person who earns the income. By contrast, indirect taxes are collected from someone other than the person ostensibly responsible for paying the taxes. In law, the terms may have different meanings. In U.S. constitutional law, for instance, direct taxes refer to poll taxes and property taxes, which are based on simple existence or ownership. Indirect taxes are imposed on rights, privileges, and activities. Thus, a tax on the sale of property would be considered an indirect tax, whereas the tax on simply owning the property itself would be a direct tax. The distinction can be subtle between direct and indirect taxation, but can be important under the law.

Proportional, progressive, and regressive

Proportional, progressive, and regressive

An important feature of tax systems is the percentage of the tax burden as it relates to income or consumption. The terms progressive, regressive, and proportional are used to describe the way the rate progresses from low to high, from high to low, or proportionally. The terms describe a distribution effect, which can be applied to any type of tax system (income or consumption) that meets the definition. A progressive tax is a tax imposed so that the effective tax rate increases as the amount to which the rate is applied increases. The opposite of a progressive tax is a regressive tax, where the effective tax rate decreases as the amount to which the rate is applied increases. In between is a proportional tax, where the effective tax rate is fixed, while the amount to which the rate is applied increases. The terms can also be used to apply meaning to the taxation of select consumption, such as a tax on luxury goods and the exemption of basic necessities may be described as having progressive effects as it increases a tax burden on high end consumption and decreases a tax burden on low end consumption.[6][7][8]

The Four "R"s

The Four "R"s

Taxation has four main purposes or effects: Revenue, Redistribution, Repricing, and Representation.[3]

The main purpose is revenue: taxes raise money to spend on roads, schools and hospitals, and on more indirect government functions like market regulation or legal systems. This is the most widely known function.[3]

A second is redistribution. Normally, this means transferring wealth from the richer sections of society to poorer sections.

A third purpose of taxation is repricing. Taxes are levied to address externalities: tobacco is taxed, for example, to discourage smoking, and many people advocate policies such as implementing a carbon tax.[3]

A fourth, consequential effect of taxation in its historical setting has been representation.[3] The American revolutionary slogan "no taxation without representation" implied this: rulers tax citizens, and citizens demand accountability from their rulers as the other part of this bargain. Several studies have shown that direct taxation (such as income taxes) generates the greatest degree of accountability and better governance, while indirect taxation tends to have smaller effects.[4][5]

Purposes and effects

Purposes and effects

Funds provided by taxation have been used by states and their functional equivalents throughout history to carry out many functions. Some of these include expenditures on war, the enforcement of law and public order, protection of property, economic infrastructure (roads, legal tender, enforcement of contracts, etc.), public works, social engineering, and the operation of government itself. Governments also use taxes to fundwelfare and public services. These services can include education systems, health care systems, pensions for the elderly, unemployment benefits, and public transportation. Energy, water and waste management systems are also common public utilities. Colonial and modernizing states have also used cash taxes to draw or force reluctant subsistence producers into cash economies.

Governments use different kinds of taxes and vary the tax rates. This is done to distribute the tax burden among individuals or classes of the population involved in taxable activities, such as business, or to redistribute resources between individuals or classes in the population. Historically, the nobility were supported by taxes on the poor; modern social security systems are intended to support the poor, the disabled, or the retired by taxes on those who are still working. In addition, taxes are applied to fund foreign and military aid, to influence themacroeconomic performance of the economy (the government's strategy for doing this is called its fiscal policy - see also tax exemption), or to modify patterns of consumption or employment within an economy, by making some classes of transaction more or less attractive.

A nation's tax system is often a reflection of its communal values or the values of those in power. To create a system of taxation, a nation must make choices regarding the distribution of the tax burden—who will pay taxes and how much they will pay—and how the taxes collected will be spent. In democratic nations where the public elects those in charge of establishing the tax system, these choices reflect the type of community which the public wishes to create. In countries where the public does not have a significant amount of influence over the system of taxation, that system may be more of a reflection on the values of those in power.

The resource collected from the public through taxation is always greater than the amount which can be used by the government. The difference is called compliance cost, and includes for example the labour cost and other expenses incurred in complying with tax laws and rules. The collection of a tax in order to spend it on a specified purpose, for example collecting a tax on alcohol to pay directly for alcoholism rehabilitation centres, is called hypothecation. This practice is often disliked by finance ministers, since it reduces their freedom of action. Some economic theorists consider the concept to be intellectually dishonest since (in reality) money is fungible. Furthermore, it often happens that taxes or excises initially levied to fund some specific government programs are then later diverted to the government general fund. In some cases, such taxes are collected in fundamentally inefficient ways, for example highway tolls.

Some economists, especially neo-classical economists, argue that all taxation creates market distortion and results in economic inefficiency. They have therefore sought to identify the kind of tax system that would minimize this distortion. Also, one of every government's most fundamental duties is to administer possession and use of land in the geographic area over which it is sovereign, and it is considered economically efficient for government to recover for public purposes the additional value it creates by providing this unique service.

Since governments also resolve commercial disputes, especially in countries with common law, similar arguments are sometimes used to justify a sales tax or value added tax. Others (e.g. libertarians) argue that most or all forms of taxes are immoral due to their involuntary (and therefore eventually coercive/violent) nature. The most extreme anti-tax view is anarcho-capitalism, in which the provision of all social services should be voluntarily bought by the person(s) using them.